The Unspoken Strategy: Daoist Wisdom in China’s Business Diplomacy

The below given passage is the opening verse of the Dao De Jing (also known as the Tao Te Ching), a foundational text of Daoism attributed to Laozi (Lao Tzu). The Dao De Jing is believed to have been written around the 6th century BCE, though its precise origins remain uncertain. Laozi himself is a semi-legendary figure, traditionally described as a contemporary of Confucius, though historical records about his life are scarce and often mythologized.

The Dao De Jing was composed during a period of social and political upheaval in ancient China known as the Spring and Autumn Period. This era was marked by conflict between rival states and the decline of the Zhou dynasty’s central authority. In response to this instability, philosophical traditions like Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism emerged, each offering solutions for restoring order and harmony. While Confucianism emphasized social roles and ethical conduct, Daoism proposed a more passive and harmonious way of life, centered on aligning with the natural flow of the universe — the Dao.

The opening lines of the Dao De Jing establish a key Daoist principle: the true essence of the Dao (the fundamental way or path) is beyond words and conceptual understanding. By stating that “The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao,” Laozi warns against rigid definitions, emphasizing that ultimate truth is elusive and best grasped through intuition and inner reflection. This idea challenges conventional wisdom, advocating for humility, detachment, and openness to change.

Throughout Chinese history, the Dao De Jing has influenced not only spiritual thought but also governance, strategy, and diplomacy. Emperors, scholars, and strategists have drawn from its teachings to cultivate a philosophy of balanced leadership, flexibility, and non-aggression. The text’s emphasis on paradoxes — strength through softness, action through non-action (wu wei) — has been particularly impactful in shaping Chinese political and diplomatic thought.

The Dao De Jing has also found resonance far beyond China, inspiring global thinkers in fields ranging from psychology and leadership to environmental ethics and modern strategic theory. Its timeless wisdom continues to offer insights into how individuals, societies, and nations can achieve harmony by embracing both stability and change.

Original Text

道可道,非常道;名可名,非常名。无名天地之始,有名万物之母。故常无,欲以观其妙;常有,欲以观其徼。此两者同出而异名,同谓之玄,玄之又玄,众妙之门。

Translation

The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao;

The name that can be named is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the origin of Heaven and Earth;

The named is the mother of all things.

Thus, always without desire, one may observe its subtlety;

Always with desire, one may observe its manifestations.

These two arise together yet differ in name;

Together they are called the mystery.

Mystery upon mystery —

The gateway to all marvels.

Commentary

The passage from the Dao De Jing by Laozi offers profound insights that resonate with China’s approach to business diplomacy. In the context of global economic strategy, these ancient principles reveal key patterns in China’s diplomatic conduct, particularly in its balance of visibility, adaptability, and influence. The opening line, “The Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao,” reflects the flexibility that characterizes China’s diplomatic style. Rather than adhering to rigid frameworks, China often adopts fluid strategies that adjust to changing global dynamics. This adaptability has been crucial in navigating complex trade environments, forming alliances, and expanding economic influence.

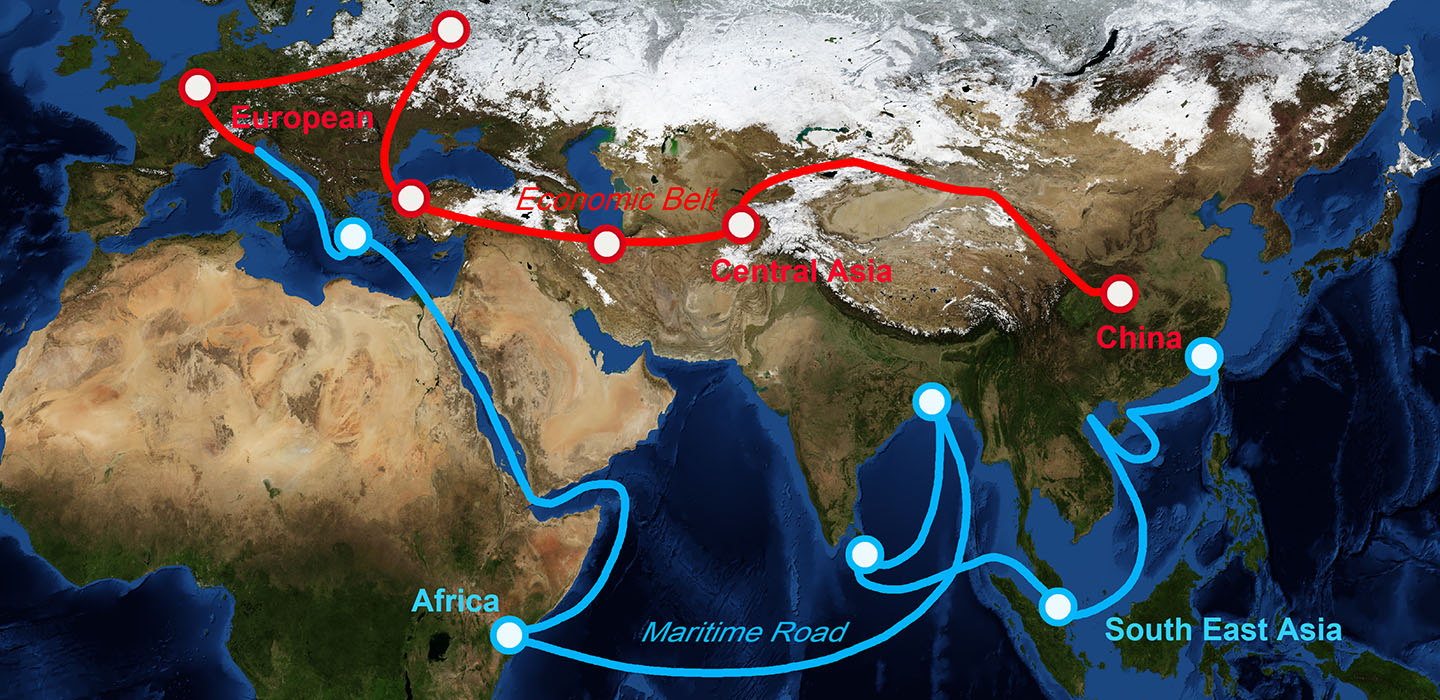

The contrast between the “nameless” (representing the unseen, fundamental force) and the “named” (the tangible and manifest) reflects how China balances visible and discreet tactics. While initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) stand out as powerful symbols of Chinese influence, much of China’s business diplomacy operates quietly, through targeted investments, technology transfers, and strategic partnerships. This twofold approach mirrors the Daoist concept that both subtlety and explicit action are essential elements of effective influence.

Laozi’s notion that “always without desire, one may observe its subtlety; always with desire, one may observe its manifestations” illustrates China’s skillful management of global economic diplomacy. China often maintains a calm, long-term perspective in trade and investment decisions, appearing patient and restrained while pursuing its larger strategic goals. This aligns with its preference for building lasting economic ties rather than focusing solely on immediate gains.

The passage’s reference to the interplay of opposites — “Mystery upon mystery, the gateway to all marvels” — suggests that China’s diplomatic success lies in embracing complexity. By blending openness with careful control, China has managed to foster economic relationships across diverse cultural and political landscapes. The Daoist wisdom reflected in this passage highlights China’s ability to harmonize seemingly conflicting approaches, positioning itself as a powerful yet adaptive force in global business diplomacy.